Canal Street confidential

Slaves of New York, My First Book, synthetic zeitgeist, thousand-yard stares

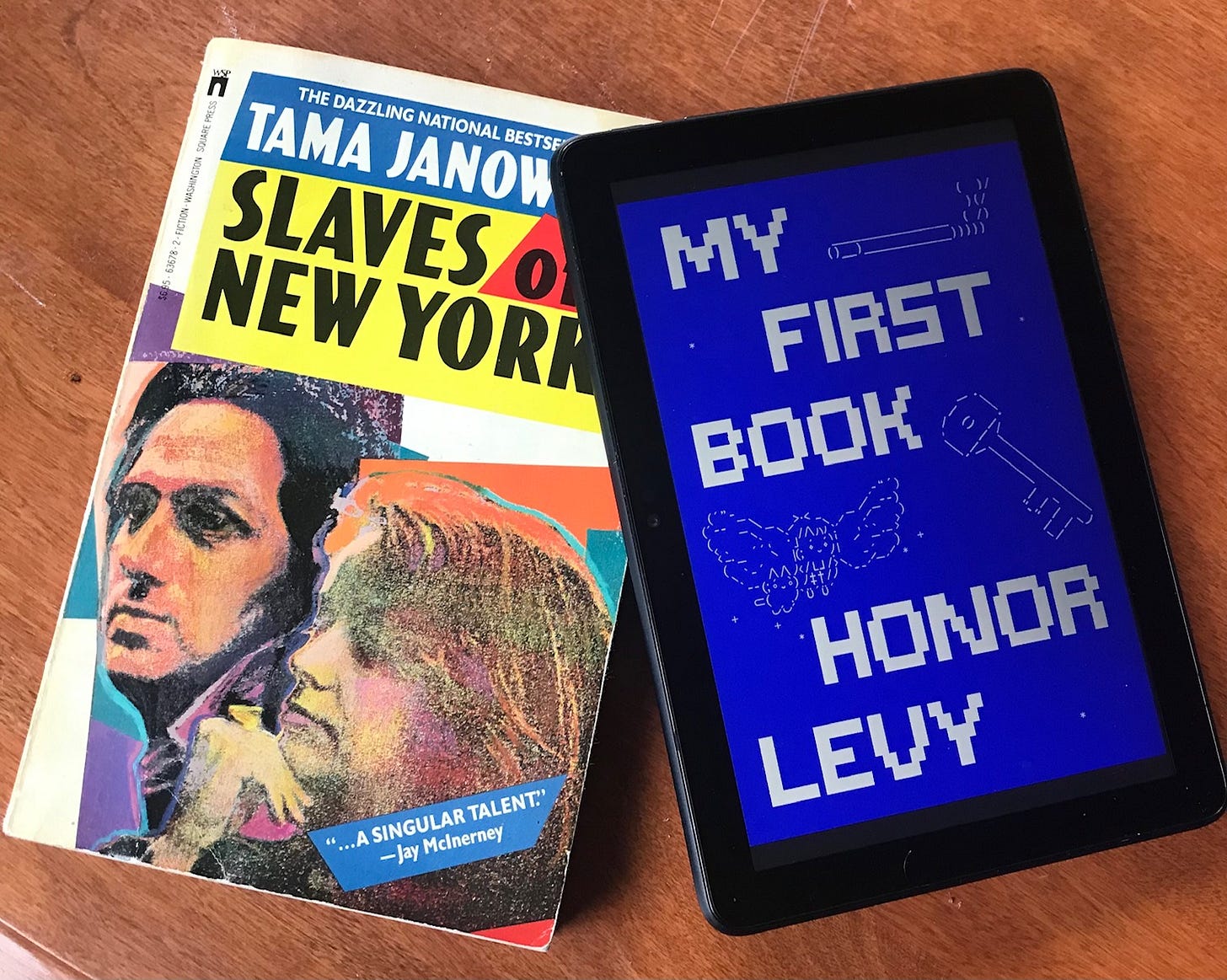

Slaves of New York

Tama Janowitz

Crown, 1986

My First Book

Honor Levy

Penguin, 2024

Sometimes it’s easier to name a phenomenon than to describe it. As early as 1987, members of the so-called Literary Brat Pack admitted it was a hoax concocted for a magazine spread. “We were strangers, or — after a few photo shoots — superficial acquaintances, a fictional ‘pack’ of fiction writers,” Jill Eisenstadt wrote. “The parallels so widely noted in our work were based on little more than circumstance.” They were young and white; a few of them had overlapped at Bennington, but didn’t really hang out. As for their legacy? Eisenstadt fell off the map after a lovely debut, Bret Ellis and Jay McInerney became Republicans, Donna Tartt became Goth J.K. Rowling. Some good books, some bad ones, nothing to peg a thesis to.

I’d been meaning to check out Tama Janowitz’s Slaves of New York for a while, but unfortunately I stumbled upon her 1981 debut American Dad first. American Dad is one of the worst novels I’ve ever read, a satire bereft of jokes and commentary. It’s like one of those Saturday Night Live skits regurgitating a meme the writers can’t compute, A Confederacy of Dunces by ChatGPT. Janowitz pivoted to short stories following the novel’s publication (“At least they don't take a whole year or two,” she told Harper’s Bazaar); The New Yorker printed five in thirteen months before Slaves of New York arrived in 1986.

That’s noteworthy from today’s vantage, because The New Yorker is no longer in the business of scouting and breaking young writers.1 Janowitz was iconoclastic in her way, depicting a corner of the city — Warhol and Basquiat’s New York — that had eluded literary fiction. Slaves of New York is a stranger book than I’d anticipated, though I’m not sure how intentional that is2: Janowitz’s plotting is haphazard, her command of language fairly poor.3 The stories are deadpan voice exercises roped together with bracing, eye-rolling cynicism.

Janowitz fails to apprehend that satire is rooted in observation, that its success hinges on specificity — before applying the magnifying glass, you must size up your targets.4 Since her characters lack backgrounds and motives, only clichés apply. Artists, they sure are broke! Apartments, they sure are small! Naturally, it gets pretty mean-spirited: the narrators punch down at hippies, queers, sex workers, and the unhoused every chance they get. (Janowitz’s subsequent novels are titled A Cannibal in Manhattan and The Male Cross-Dresser Support Group. Good one, Tama!)

Janowitz is disgusted by squalor, which is encountered deliberately throughout Slaves of New York. In pursuing creative work, the artists opt into self-imposed poverty, which makes them stunted and debased. They have childish interests and affectations, loafing around sordid apartments waiting for phone calls. The art itself becomes secondary — talented or not, those involved are chasing frivolous, arbitrary stardom.5

It’s all pretty evasive, and Janowitz takes refuge in gratuitous surrealism. In “Matches,” an otherwise mundane account of a disappointing house party, the narrator meets an infant who converses in full sentences. In “The New Acquaintances,” a repressed academic convinces a destitute woman to marry him, only to be usurped by a “highly sexed” nine-year-old who sweeps her off her feet. It’s profound if you want it to be; readers determined to find parallels with Warhol or Basquiat’s work might well find them. Applying a sociological lens, one could approach Slaves of New York like a Wharton novel documenting the gender politics of a bygone era. Janowitz’s female characters are tethered to male partners, most of them equally hapless and unemployed. They’re all slumming it.

What is it, then, about New York City? Why did The New Yorker see fit to canonize these self-impressed character sketches? The Manhattan of ‘86 is open and unpredictable. It is densely packed, a melting pot, teeming with transit, industry, and nightlife. What appeals to me is Slaves’ framing of New York as a self-contained universe — even when Janowitz’s characters decamp to the Hamptons, they can’t escape downtown’s orbit. Their jobs, relationships, even modes of speech and dress are dictated by the housing market. Speaking from experience, there comes a point where you can’t explain to your suburban friends why you’re still broke and childless.

Even still, these are insights derived on the road from Montclair to Greenwich. It’s cheap exoticism, gawking at Middle-Eastern cab drivers and same-sex couples. Janowitz was championed by publishers and editors — older, comfortable New Yorkers who no longer recognized the metropolis around them, never supposing Janowitz was a prude herself.

Which brings me to Honor Levy’s much-discussed, little-read My First Book. Levy, like Janowitz, landed an early, polemical short story in The New Yorker; she too inhabits an embellished, derided downtown scene. (Of course she went to Bennington.) In her early twenties she fell under the wing of Gian DiTrapano, the late tastemaker, literary prospector, and publisher of Tyrant Books. When DiTrapano died in 2021, his youngest protégés were scooped up by the major publishing houses, who eagerly published their works-in-progress.

The books (I’m referring now to Sean Thor Conroe’s Fuccboi as well as My First Book) stink, because Hachette and Penguin misapprehend DiTrapano’s project. DiTrapano sought compelling people and stories, writers on the margins, and — through a yearslong process of workshopping, editing, and mentorship — teased books out of them. The Tyrant books could be tricky, because for all their structural informalities they were governed by romantic nostalgia. DiTrapano was serious about literature, intent on publishing novels. Penguin, on the other hand, is enamored by Levy’s celebrity; in an age of winnowing margins, she supplies a built-in audience. DiTrapano would not have published My First Book, not in this form. When you press 500 paperbacks to ship from your apartment, there’s no use for gimmicks.

From a publishing standpoint, this is as cynical and futile as it gets. A quick survey of social media would confirm Levy’s niche following. Perhaps it’s easier to market Levy than some unknown MFA grad, but the ceiling is lower — if that MFA grad breaks out, it’ll be because her writing’s actually good. And even supposing My First Book were a trenchant meditation on online identity and the post-post-politics of pandemicene Manhattan, why would Penguin bother? Emily Ratajkowski published a book of Didion-voice essays about her tits, and even that flopped.

In a 1987 Los Angeles Times article heralding the Literary Brat Pack, Nikki Finke backhanded, “They write slim volumes or short stories, the perfect medium for an MTV-nurtured generation with a short attention span.” My First Book doubles down: if zoomers’ brains have been fried by smartphones and stimulants, they can only digest literature in bites. I’m not suggesting Levy’s subjects are invalid — the internet is increasingly processed in the analog world, rather than vice versa — but the format is rarely justified. If a book emulates the experience of TikTok, wouldn’t I just go on TikTok?

The buzziest stories here dramatize web relationships, the gulfs between flesh-and-blood demography and pixelated avatars. But in My First Book, as on the internet, everyone — the charismatic misogynists in “Good Boys,” the Rogan-pilled bodybuilders in “Love Story” and “Brief Interview with Beautiful Boy” — is a Type of Guy. Levy’s characters inhabit Instagram, Reddit, Snap, and TikTok with varying degrees of anonymity, bored in their dorm rooms and childhood homes. There’s no subculture or tribal knowledge: Levy’s internet is a Zuckerbergian monolith, where everyone acts in familiar, foreseeable ways. Nudes are requested and delivered, memes are based, activism is cringe. Levy may as well be rattling off the names of network television shows.

“Cancel Me” reheats the devil’s advocacy of Natasha Stagg’s “Two Stops,” which appeared in n+1 at the height of #MeToo. “A shitty man is not necessarily dangerous, and writing his name onto a Google spreadsheet does not make you a good person,” Levy declaims. “The men yelling at you on the street corner in Bushwick probably do not want to rape you.” The throat-clearing over purity tests (“I’m afraid of self-censorship”) evolves into apologia: Aren’t we supposed to like bad boys? Isn’t that what it means to be feminine, to be feminist? If not, isn’t feminism cringe? Fourth-wave feminists are not, in any event, having the type of sex one seeks in Dimes Square when you’ve had two glasses of wine, one Xanax, the sun descending over the Manhattan Bridge, and you want to live, but also die.

This is mask-off publishing, craven and predictable. The uprising of 2020 barely lasted a summer; we’re years into a backlash that’s permeated every echelon of culture and commerce. DEI officers were sent packing, cops are more emboldened than ever, Trump’s about to win 230 electoral votes for the third time in a row. Publishers are no longer imploring us to decolonize our shelves; good luck finding the Nigerian novels at Books-A-Million. My First Book presents handsy men and hate speech as things to be entertained, if not encouraged. For Levy and her friends, it’s easier that way.

There’s genuine despair here, anguish over being reduced to lines of code, judged by selfies and taste in memes. But it’s couched in irony and ennui; like Janowitz, Levy can’t look her reader in the eye. She has no traits besides those conditioned by the internet, and is proud of it. Maybe society did this, maybe our parents (too protective, or else too laissez-faire), maybe we did it to ourselves. You could log off, but staying online is easier.

Dwight Garner gave My First Book a thumbs up, which isn’t the brave endorsement he thinks it is. This is how the Big Five publishers are courting Gen Z; Garner will be on the side of history. If he had any curiosity at all he’d have encountered more accomplished writers on Tumblr, on Substack, in undergraduate journals. But then Levy isn’t creating or capturing a new vernacular so much as condensing it for the appraisal of a literary establishment. Behold, Dwight Garner, silver-haired New Yorker subscribers, professors of comparative literature: this is how The Youth speak on their computers. Supposing My First Book were intended for an audience of Levy’s peers, it becomes a meaningless exercise. We already know how people communicate online, we’re literally stuck here.

It’s striking how similar Janowitz and Levy’s trajectories have been, given how much everything else has changed in 38 years. Janowitz’s peers were able to mess up and grow up, publishing schlocky juvenilia en route to careers as serious novelists. Jay McInerney is the beau ideal: celebrated for his promise, he would write masterful novels in his forties and fifties, yet remains beloved for his flawed, early output. Such a career is unimaginable today — when a debut flops, you’re relegated to the minor leagues.

From an agent or editor’s perspective, Janowitz and Levy could be shaped for the same niche. These willowy, hidebound white women — “culturally” Jewish, if anyone asks — with vague cachet south of Houston Street: There might be something here. And that’s the whole pitch. Their messy books would epitomize messy youth, and readers would hold them to low standards. Is Honor Levy a precocious child, or is she the same age as — to pick one example at random — Harold Brodkey when he published First Love and Other Sorrows? Both can’t be true, and if Janowitz is any indication, there’s no where to go from here. After printing five of her stories between December 1984 and January 1986, The New Yorker never published Janowitz again. The players change, and the game remains.

They’re happy to let agents and smaller journals do their dirty work.

I’ve been thinking about this Becca Rothfeld post, specifically the paragraph below, which is in reference to Sally Rooney but applies as well (for my purposes) to Janowitz and Levy:

I feel like there is a certain kind of tic so common in contemporary criticism that it deserves a name. The tic goes like this: a critic can’t entirely extirpate an abiding fondness for a novel she cannot really justify liking, so she attempts to transmute the novel’s vices into virtues by claiming that the book is bad on purpose, e.g., this novel about life online is boring and sterile and cynical on purpose because life online is itself so boring and sterile and cynical. Maybe the novel in question is boring and sterile and cynical on purpose, but who cares? Either way, it’s boring and sterile and cynical—and therefore not very good.

Per Elwin Cotman: “In Janowitzland, artists in toxic relationships are the slaves of New York, and this is, prior to another writer calling slavery a choice, the most obtuse line I’ve read on the subject.”

I’m reminded of this really sharp

post, in which considers the deteriorating concept of satire among younger internet users. Referencing TikTok creator Henry De Tolla’s oeuvre (which does not, to my sensibilities, evince any semblance of humor or commentary), Read posits that there’s a “special Zoomer definition of ‘satire,’ which means something like ‘I said something I didn’t really believe to provoke some kind of reaction on social media.’”Read continues:

I think of satire as a kind of humor with a particular target, which I’m not sure the De Tolla videos have. From what I could tell his main goal was to build an audience (among middle schoolers, he says), not to undertake social criticism through the deployment of wit, or whatever. What Zoomers like to call “satire”--saying stuff you don’t really believe to provoke negative reactions on social media to expand your audience--I tend to call “bait.” I suppose you might say that bait can function as satire, but whatever social criticism it generates is an accident. The main point is to get people watching, sharing, and talking about your content.

This isn’t exactly what Janowitz does in American Dad and Slaves of New York, but it’s not far off — they’re shaped like satires, but as books they’re empty, humorless husks. Like De Tolla’s videos, they’re vehicles for empty-calorie surrealism instead of, like, actual jokes. One could argue Levy has even more in common with De Tolla, in terms of voicing ideas she doesn’t believe in order to provoke reaction; the ostensibly fictional conceit of My First Book provides cover. Which is to say, you can pass off a lot of bullshit by calling it satire.

Jay McInerney, later in his career, was accused of loving his own characters too much, a charge I never understood — sympathy is what separates fiction from journalism. Granted, his portraits of Manhattan’s upper crust are clubby and tribal, naïve if not overtly propagandistic (I imagine this sympathy informs his real-life politics, which are bad, and beyond this footnote’s purview). The man loves life in New York City; his romanticism is infectious. Is that a sin? Well, Janowitz hates the city and people she writes about, for no apparent reason. Go off!

I reread Slaves of New York this summer and it was even better than I remembered from when I first read these stories in the 80s. It’s a really funny book, equal to Bright Lights Big City. There’s a fragility and vulnerability beneath the humor. If it is satire it’s more of a gentle social satire than the mocking satire of Gentlemen Prefer Blondes (although I like that one too).

Oh, for a young writer willing to fail as floridly and epically as Brodkey. Have you ever listened to Richard Ford’s episode of the New Yorker fiction podcast where he reads “The State of Grace?” (His gloss on it is probably better than the story itself.)