Pen Pals: Jo Hamya

"It would be ridiculous of me to call my youth an obstacle. Personally speaking though, I find it embarrassing."

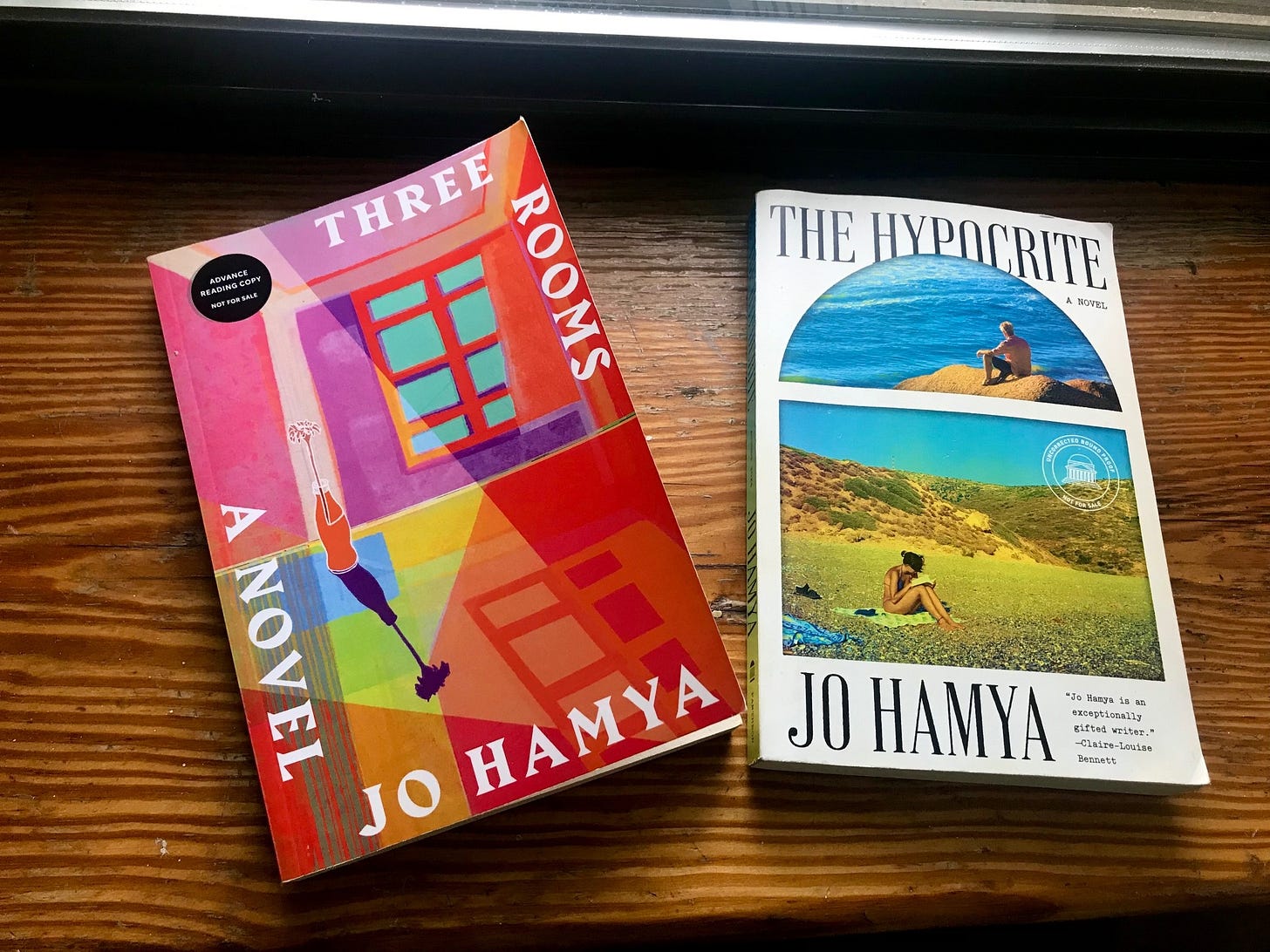

At 26, Jo Hamya’s already published two of the most striking, stylish literary novels of the 2020s. Her 2021 debut Three Rooms, a frank, unsentimental lament of a social novel, dramatizes the housing crisis through the eyes of a British graduate student. Imbuing first-person methods with material analysis, Hamya captures the lived mundanity of economic collapse; weighing social opportunities against a lack of mobility, her narrator finds meager privilege in self-analysis.

Although Hamya’s second book The Hypocrite — out now in the U.K., coming to the U.S. August 13 — takes place in a single afternoon, its metafictional narrative chronicles the dissolution and recalibration of a nuclear family. Sophia, a twenty-something playwright and daughter of a successful novelist, has composed a play based on a Mediterranean summer spent with her father a decade prior. Lambasting her father and his politics, the play debuts midway through 2020 as Sophia’s parents attempt reconciliation. An accumulation of grievances, resentment, and filth — bodily and emotional — the play tilts the family’s uneasy axis, foregrounding incisive class commentary.

Hamya is pursuing a PhD at King’s College London, and hosts the Booker Prize Podcast with critic James Walton. In our email correspondence, Jo and I discuss The Hypocrite’s genesis, creative inheritance, and her transatlantic education.

Pete: The Hypocrite has a really unique, nested structure, a novel within a play within a novel. How did you arrive at the metafictional format? While writing, did you find the discrete narratives influenced one another?

Jo: I wish I had a more sophisticated answer but the form presented itself to me in tandem with the idea for the book, and the seeming impossibility of it was immediately seductive. I felt that if I could learn how to pull it off, I would become a better writer. So I didn’t so much arrive at it as set it as an end goal — to finish with a book that was fluid and cohesive despite the Russian doll format, and the formal/logistical complexity that implied.

And I knew from the start that each narrative would lock into and propel the others around it. The appeal of a metafictional device was that it allowed characters to engage in acts of interpretation about each other without any need for outright exposition on my part; it allowed for contradictions between what they said to each other and what they did via their own creative acts. Each narrative had to be a form of retelling — like exposing photos on top of one another until a unique image is generated. Not to pile metaphors on too thickly, but that image then turns into a Rorschach test for each individual reader. I knew I’d never have to make any sort of moral pronouncements in the book because the form would drive readers to do so themselves. What I was interested in was what kind of pronouncement they would arrive at when it was all over.

Pete: The Hypocrite captures this strange period during the first year of the pandemic, when mitigation efforts were relaxed mere weeks after deaths had peaked. Many of the characters flout COVID protocols, often for their own leisure or convenience. Did it feel important to document this moment, and the — dare I say — hypocrisy of public health policies? Were you conscious of how these passages might read in the future, as COVID is increasingly referred to in the past tense?

Jo: COVID seemed like a perfect backdrop to a story about characters who got locked into their own generational worldview to the point of estrangement whilst still having to care for each other because the pandemic itself replicated that circumstance. In order to care for the lives of the people around you, you had to have as little contact with them as possible. A lot of life started happening online. Everything felt heightened and extremely high-stakes. But I didn’t want it to be a pandemic novel — more, a document of how certain pre-existing sensibilities became temporarily radicalised in that time.

Lockdown protocols in the U.K. were a joke, and very useful for the plot I’d established. Theatres did reopen for a few weeks in July and August at 50% capacity. If you lived alone, you were allowed to mix with one other household to maintain your mental health. Our then Chancellor of the Exchequer, now ex-Prime Minister financially incentivised people to eat out at restaurants, to get take out delivered to them by vulnerable gig workers. The amazing thing is — none of the characters in this book actually flout lockdown protocol at any point (or only in some places where they forget to wear face coverings). At the time, I think a lot of people felt their personal freedoms had been excessively curtailed. It’ll be interesting to see whether future readers think they were, in fact, not restricted enough.

Pete: Sophia’s father is a rollicking, twentieth-century male novelist, whose politics are deemed questionable by younger readers. Was his a difficult perspective to inhabit? Did you read or consume any material to help inform his voice?

Jo: I loved writing Sophia’s father. It took a third of the first draft to realise his voice was intimately familiar to me. I’ve been reading it my whole life. For my final secondary school exams in England, I had to read W.B. Yeats, and the practice exam questions were things like, How does Yeats’ perspective on aging and mortality change from ‘The Lake Isle of Innisfree’ to ‘The Tower’, or, ‘Compare and contrast Yeats’ portrayal of romance in ‘The Wild Swans at Coole’ and ‘Leda and the Swan’. It’s marvellous to remember being sat in a room with ten or twelve 17 year-old-girls forced to decipher the psychosexual and existential concerns of a dead Irish man. When I went to university and realised I wanted to work with books somehow, I began reading trade periodicals — The London Review of Books, or the TLS — which all esteemed that same kind of figure you mention.

It was excessively fun to inhabit a place of freedom and success and uninhibited fun that those 20th century male authors enjoyed despite the fact that some of it created a hostile environment for women, or non-white workers. In real life, I’m tortured by the financial precarity of writing; the occasional fear of saying the wrong thing, the limitations those things place on me. The fact is that those men do write very well, and they did ignite parts of my imagination growing up. It bears saying that U.K. publishing is now dominated by women in their 30s and 40s and questions regarding pay equality and representation are still fraught. And it was equally heartening to discover that I developed real sympathy for Sophia’s father: he spends the novel falling apart. His whole world-view is collapsing against his will. His daughter might not like him. I think it would have been disingenuous not to be able to write his predicament with care because I have different socio-political views.

Pete: Both of your novels deal with themes of creative inheritance. In Three Rooms, Ghislane assumes the role of art-world ingenue thanks to her rock-star father, and in The Hypocrite, Sophia leverages her access to rebuke her father’s novels. I found a number of parallels between these women and the shadows cast by their fathers — Ghislane and Sophia voice distaste for their fathers’ work, yet seem unable or unwilling to pursue ideas of their own. Do you feel sympathy for artists whose names precede them? Do you think art — the material, the substance, the output — ever benefits from this sort of associative privilege?

Jo: I’m so pleased to finally be asked for my take on nepo-baby discourse. Truthfully, I didn’t intend to write about it, I’m just very interested in questions of lineage, possession and reinterpretation: I think they’re quintessentially British themes born out of monarchy, Empire, and the very particular way wealth is hoarded in this country. That’s not to conflate Sophia or Ghislane’s narratives with those exact concerns, but I think being brought up in Britain trains you to think about those things in one form or another — this has been mine. And I like writing about the gulf between the upper classes and middle classes because the past two decades of economic policy here have resulted in the latter’s simultaneous expansion and impoverishment. More people are middle class than ever, and yet they enjoy fewer privileges associated with the classification (home-ownership, job security, debt-free education). Ghislane and Sophia have the potential for a kind of inherited happiness, or inherited security at the very least.

Re art, and in abstract, I probably have a softer stance on creative inheritance and the failed pursuit of something original. The early drafts of all my fiction steal shamelessly from musicians and poets; I rework those lines over and over again until they’re mine. I’m not convinced that ‘pursuing ideas of your own’ is as rewarding or virtuous a project as it sounds. I like when concepts are in conversation with one another; reimagined, re-contextualised. That impulse is celebrated everywhere except literature — fashion loves to reinvent the little black dress; musicians love to sample; film-makers love to reference scenes from other movies. And audiences are excited to recognise those gestures, whether because they’re an expression of love, or admiration, or powerful dissent. Sometimes it’s just fun to spot easter eggs. I’m fairly ambivalent about nepotism in the arts. It would be nice for literary advances not to be determined by a prospective writer’s social media stats, but that’s not exclusive to who your parents are.

Pete: There’s a passage in Three Rooms I enjoy, where the narrator is living in London and reading a sequence of recognizable contemporary novels — spare, contemplative books by women authors, unpacking the narrators’ inner lives. You’ve mentioned elsewhere you don’t consider Three Rooms a work of autofiction — do you consider it a work in conversation with any other novels? Was there anything you wanted to pay tribute to, or any pitfalls you made a point of avoiding?

Jo: Three Rooms is indebted to Woolf’s A Room of One’s Own: I pulled her basic structure (abstract to real; Oxbridge to London) and applied her themes to my contemporary moment. It also owes a creative debt to Andrew Motion’s Essex Clay, Hannah Sullivan’s Three Poems, Wordsworth’s The Prelude, Jhumpa Lahiri’s In Other Words, Anne Carson’s Glass and God, and Rachel Cusk’s Transit: I read and re-read those books in order to carve out a style that worked for me, and they all tackle the question of identity in relation to space in novel, brilliant ways.

I don’t consider Three Rooms autofiction because I spent all the time it took to write suppressing the fear that people would think the narrator was me in order to finish it. Of course, they did. The U.K. jacket didn’t help — it wasn’t a very wise choice, for many reasons. But I wasn’t trying to illuminate my identity or experience to myself or others — I just felt I’d accumulated a lot of interesting material at Oxford and the society magazine I subsequently worked at. I felt I could say something interesting about the state of the nation with it. I didn’t have the nous to repurpose or fictionalise the details properly. I wrote the book at 22, and it was my first real attempt at a novel. I was more concerned with establishing what good writing meant when I was the one doing it. I doubted it would ever be published: it was my unemployment project. For that reason, I didn’t explicitly think about pitfalls, either. I didn’t know I had to. I liked poking fun at those spare, plotless novels by women because I knew I was repurposing a form I loved for my own end. I was trying to kill my darlings.

That being said, I had a very intense admiration for autofiction and adjacent forms at the time, like Levy’s ‘Living Autobiography’ (though I do wonder how an autobiography can be otherwise). I wish I’d been less strong in my refutation of them then. I was excessively defensive, thanks to being 23 around the time of publication, but the truth is, it was a generative genre to read for the social realism I ended up wanting to write. I should have said that instead of having a tantrum.

Pete: When it came to marketing and selling your novels, did you find your youth to be an advantage or an obstacle?

Jo: I think there’s no doubt that the U.K. publishing market privileges bright, shiny young things. It would be ridiculous of me to call my youth an obstacle. Personally speaking though, I find it embarrassing.

Pete: I read you spent some time in Florida growing up? Did you attend school there? Did your time in the U.S. influence your paths in writing and academia?

Jo: I did, from ages 13 to 16. I went to Palmetto Senior High. I think I got bumped up a grade or two, which was fabulous because it meant my friends could drive me to the mall on weekends.

I owe a large part of my intellect to the American education system: secondary school and sixth form equivalents in England are terrible. Performance is measured with one-off exams at the end of a given period of years, which means students can only succeed via rote memory learning done according to the specifications of two or three examination boards. Passing means you’ve essentially become a very successful parrot: you know what words to say, in what order, and to what effect — ostensibly, you don’t even need to understand what they mean. Having a cumulative, weighted grade point average in the U.S. meant you got assessed fairly on multiple fronts: pop quizzes for understanding, homework for progressive learning, participation for effort, research projects where you could develop your own sense of things, and so on. It also meant you had the space to give your opinion on what you were being taught. High school was hard work, but it was imaginatively rewarding — you can’t imagine how shocked I was coming back to the U.K. to find that the mode of opinionated free thinking I’d developed would cause me to fail my exams. I was explicitly told not to write my own thoughts down, to copy whatever my textbooks and teachers said.

I resented school in England after America. You’d be given three weeks to copy and paste an 1,000 word essay from a pre-established spec. I was used to four hours of homework a night in which I had to develop an actual skill, world view, or understanding of the topic at hand. I took extra subjects but I was still bored. I cut classes to walk around town on my own. No one ever brought me up on it properly because it turned out I’d already gained enough qualifications for university in the States thanks to AP classes; I was just too young to go. I read whatever I could buy from the only shabby little stationers-slash-bookshop near me at the time whilst skipping lessons: Wuthering Heights; Eleanor Catton’s The Luminaries; Julian Barnes’ The Sense of an Ending; Virginia Woolf, Dostoyevsky. Which makes me sound like a saint, but I also walked aimlessly around the area and drank cheap cider in the park and got smashed at house parties. That time seemed endless because most of my fellow students were cliquier and bitchier than in the U.S., but it was actually only two years. So I have a lot to thank American high school for: I don’t know that I’d have achieved the things I have without it. The students and teachers there were very kind to me, and I found myself emboldened in ways I never could have been in England.

I enjoyed Jo Hamya's comments about using others' words until they become one's own--and her rarer comments in appreciation of her American high school education. Thank you for your introduction to an intriguing young author.