Pen Pals: Joseph Rathgeber

"We’re all fucked. But there’s a grim poetry to it that I can muse about in the moments between crying jags."

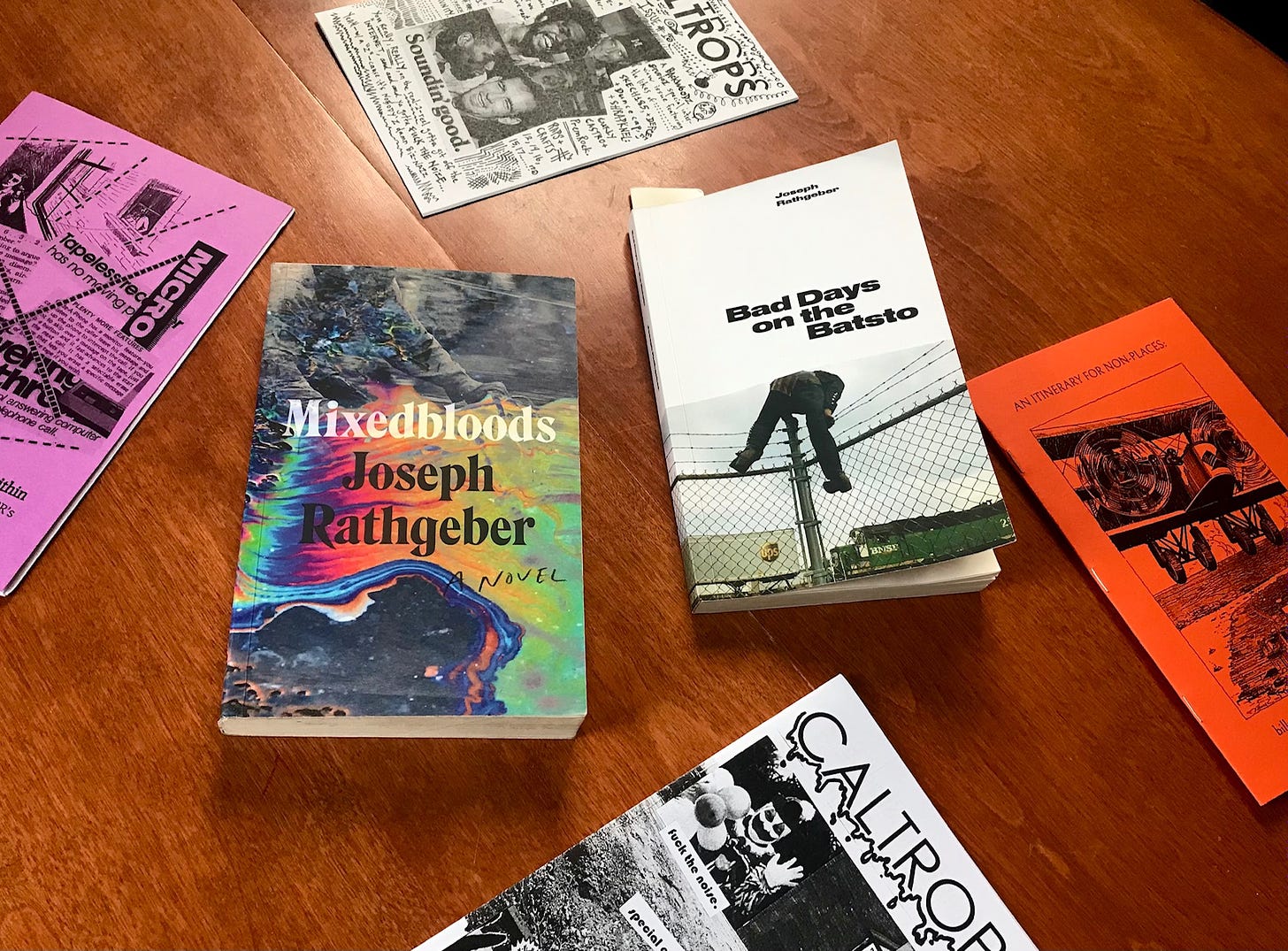

I met Joseph Rathgeber by chance in 2019, and a few weeks later he mailed me a copy of his novel Mixedbloods. I devoured it during the earliest days of the pandemic, tucked away on a park bench, enraptured by the ruined characters and hyper-local detail — it’s one of my favorite books of the last decade.

It was another four years before I, in my great ignorance, learned Joe was the man behind the Caltrops Press zine series. True to its tagline (“fuck the noise. get off the internet”), Caltrops is an analog experience, cataloging the triumphs of Armand Hammer, Fatboi Sharif, and rap’s most brilliant outsiders. Its hand-to-hand circulation reflects a bygone DIY ethic, linking out-of-print texts with outer-outer-borough performance spaces. It isn’t really criticism, or journalism for that matter — Joe is a scholar-poet, delving into minutia, heeding echoes across mediums and generations.

Joe’s received two poetry grants from the New Jersey State Council on the Arts, as well as an NEA fellowship for his short fiction. His latest story collection Bad Days on the Batsto embodies a disappearing American regionalism, capturing the industry, leisure, and culture wars of contemporary New Jersey. A multiracial chorus of voices on both sides of the poverty line, the characters seek transcendence, annihilation, or both. The twelve stories depict life alongside highways and contaminated backwaters: the radiation will kill you if boredom doesn’t get you first.

Joe was nice enough to indulge me in the email exchange below. In our long-overdue conversation, we discuss New Jersey’s cultural outputs, Backwoodz Studioz, and Joe’s journeys in writing and publishing.

Pete: Hey, Joe. Glad for the opportunity to discuss your work, and apologies for not doing this sooner. To set the scene, I believe we met in summer 2019? I’d published some book reviews in newspapers, and Bud Smith — a novelist I really respect — invited me, out of the blue, to a reading at KGB Bar. He read from an early draft of Teenager; I introduced myself after the reading, he introduced me to you, and a few weeks later you sent me a copy of Mixedbloods.

I should caveat all this for objectivity’s sake. I can count on one hand the number of readings I’ve attended in New York; it was my first and last time at KGB Bar; it was the most literary-scene thing I’ve ever participated in. (And boy has the newspaper work dried up.) It wasn’t until sometime last year I realized you were the writer behind Caltrops, which I should’ve figured out a long time ago.

Since Mixedbloods was my official introduction to your work, can we start there? To summarize for our readers, the Ramapough Lenape have occupied what is now New Jersey and New York State for hundreds of years. But because they happened to live right where the Dutch landed, they’re considered multiracial and the federal government doesn’t recognize them. Mixedbloods dramatizes this conundrum — that of a real-world lost tribe, invaded and ostracized by settlers, without even the grim consolation of tribal reparations. Can you tell me about your entree into the community, and how Mixedbloods presented itself as a story?

Joe: The timeline of your memory of us meeting is accurate. That visit to KGB Bar was an aberration for me too. I was in attendance because I thought it would be a good opportunity to hand-deliver a copy of my novel to Bud. He was kind enough to read a draft of the book and provide a blurb. I don’t know him that well, but the impression I get is that he’s a genuine guy, which is difficult to come by in writerland. The fact that he’s from New Jersey is an added perk. I can’t remember how we first connected, but I know I initially came across his name in this obscure Jersey-based lit mag called The Idiom. We both had some poems published in there. I think I probably just reached out via email at some point. I respect him because he was able to grind his way to the top of this lit shit. He wrote, and wrote, and wrote — and then he read, and read, and read publicly — and he made enough friends and endeared himself to enough important people to get into The Paris Review and secure a book deal. That motherfucker doesn’t even have an MFA. I appreciate anyone who circumvents the traditional channels of publishing. He made his own way, so shout-out to him.

I think I remember just walking up to the bar where he was talking to you after he read. (I was anxious to get out of there.) He immediately introduced me to you, and I probably heard “critic” and immediately offered to send you my book. I was desperate for anyone to read the thing at that time. I’d put so much into it, and I knew it was gonna drop with a thud. When you made the connection between me and Caltrops last year, you said such nice things about the novel. There have been a handful of sincere compliments people have made about it, so I carry those with me through the oceans of silence.

Growing up in North Jersey, I’d heard mutterings of the “Jackson Whites” (the derogatory term commonly applied to the Ramapough Lenape) for most of my adolescent and adult life. I’d read some very sensationalistic and downright racist opinions about the Ramapough in places like Weird NJ magazine and comments sections of news articles. One night on HBO I saw a documentary called Mann V. Ford, which schooled me on an aspect of the Ramapough I’d never heard about — that of the decades-long environmental racism they’d been subjected to as a result of Ford Motor Company’s disregard for their humanity. And, finally, I became an unwitting audience to an anecdote about some young people driving through Ramapough land to thrill-seek and terrorize. Those exposures combined to give me the idea for a novel where I might spin a character-rich narrative that would touch on themes of [mis-]identity through a teenager whose very understanding of himself can’t be severed from media representation, micro-aggressive gossip, hyper-aggressive harassment, anthropological treatises, and family and tribal oral tradition and belief.

I knew that by writing the book I’d be adding to the body of texts that represents rather than allows the Ramapough to simply exist on their own terms. I aimed to use language as a way to heighten this self-awareness in a quasi-metafictional way. I put together a polyglot potluck [if this were the novel, I’d probably say potlatch, to prove the point] of anthropological terminology, indigenous words and variations from myriad tribes, unnecessarily precise names of flora and fauna, slang, pop culture, and the lore and legends of unreliable sources.

The book was all very postmodern in these respects, though it probably doesn’t present to many readers as a “postmodern novel.” Ultimately, it was a risk I was willing to take. Despite what I do with theme and language, I don’t think of the book as a postmodern novel but as a social novel. It was my hope that Mixedbloods would bring awareness to the ongoing plight of the Ramapough. Victor Hugo said books of this nature cannot fail to be of use. Here’s hoping he was right.

Pete: Your settings often incorporate ruined ecology: polluted waterways, toxic waste sites, moldering industrial spaces. How critical are these settings to understanding the culture and attitudes of New Jersey?

Joe: My first collection of short stories had an epigraph from Junot Díaz: “Pollutants have made Jersey sunsets one of the wonders of the world. Point it out.” I’ve always embraced the idea of pointing out that duality, but it’s not unique to Jersey, of course. Things appear doomish for all citizens of the world. I was looking at aerial photographs of pink hog lagoons in North Carolina the other day, for instance. The fetid stench of pig waste permeates rural Black communities. They “can’t deal with the swine” like Sadat X said on “Ragtime.” It’s depressing.

A second epigraph from that same book has James Baldwin describing New Jersey as “one of the lowest and most obscene circles of Hell.” New Jersey has this reputation — the origins of which I don’t precisely know — as the “armpit of America” or whatever. Like most caricatures, it’s a bit cruel and more than a little close-minded. I like to facetiously talk about New Jersey as the center of the universe, but I’m also somewhat sincere about that. My fondness for New Jersey and its manifold landscapes is genuine. In the shadow of New York, there’s a beautiful loser quality to the state.

I think when people visualize New Jersey, they think of an industrial wasteland. They don’t think about the natural beauty found here. Even still, so much of the ecological devastation is invisible. You can wander the woods of the Ramapo Mountains and not once think about the toxic Ford paint sludge that might be underfoot. You can write your name upon the strand in Long Branch until the waves bring in a plastic bag or hypodermic needle. Again, we’re all fucked. But there’s a grim poetry to it that I can muse about in the moments between crying jags. My wife says that the Parkway conceals pollution and the Turnpike exposes it.

There’s this Sopranos episode where Tony, Paulie, and Christopher are returning from an overseas business trip. The majority of the episode takes place in Italy, and all its splendor is on full display. At the end of the episode, we’re in an idling car outside Terminal C at Newark Airport. The car drives along Route 21, which runs beside the most contaminated stretch of the Passaic River — a body of water where the Diamond Alkali plant dumped countless barrels of Agent Orange directly into the river at the conclusion of the Vietnam War. We see the iron lattice-work of bridges, graffiti-covered concrete overpasses, factory smokestacks, potholed roads, mounds of dirt and rubble, overgrown vegetation…and it’s beautiful. Tony, Paulie, and Christopher gaze longingly at the scenes flashing by outside their windows. It’s home, and they’ll take it over Mount Vesuvius, the Cave of the Sibyl, and the harbor in Naples any day.

So these settings I choose to depict are only critical to understand the culture and attitudes of New Jersey insofar as we’re the state that often gets pinned with the rep for ruin. But it’s not exclusive to us. Everyone can relate to the ravages. But in terms of the work, these settings help complicate plot or character; they add depth and tragicomic elements. The protagonists choose to live here despite the risks — that says a lot. Then again, I’ve seen people fishing in that portion of the Passaic, so maybe some folks just don’t know.

Pete: A few of the stories in Bad Days on the Batsto reference Keansburg — either as a setting, or just in passing — and I have a rather specific experience of the place. Among my grandparents’ demographic it was evidently this thriving Italian beach community, because there was a ferry from the West Side of Manhattan, and all these people who lived in tenements somehow managed to build themselves summer cottages. The ferry, of course, is long gone, and now it’s a bunch of throttled highways going in every direction, but I still hear the stories. What is it about Keansburg? Is it, like, the most Jersey place in New Jersey?

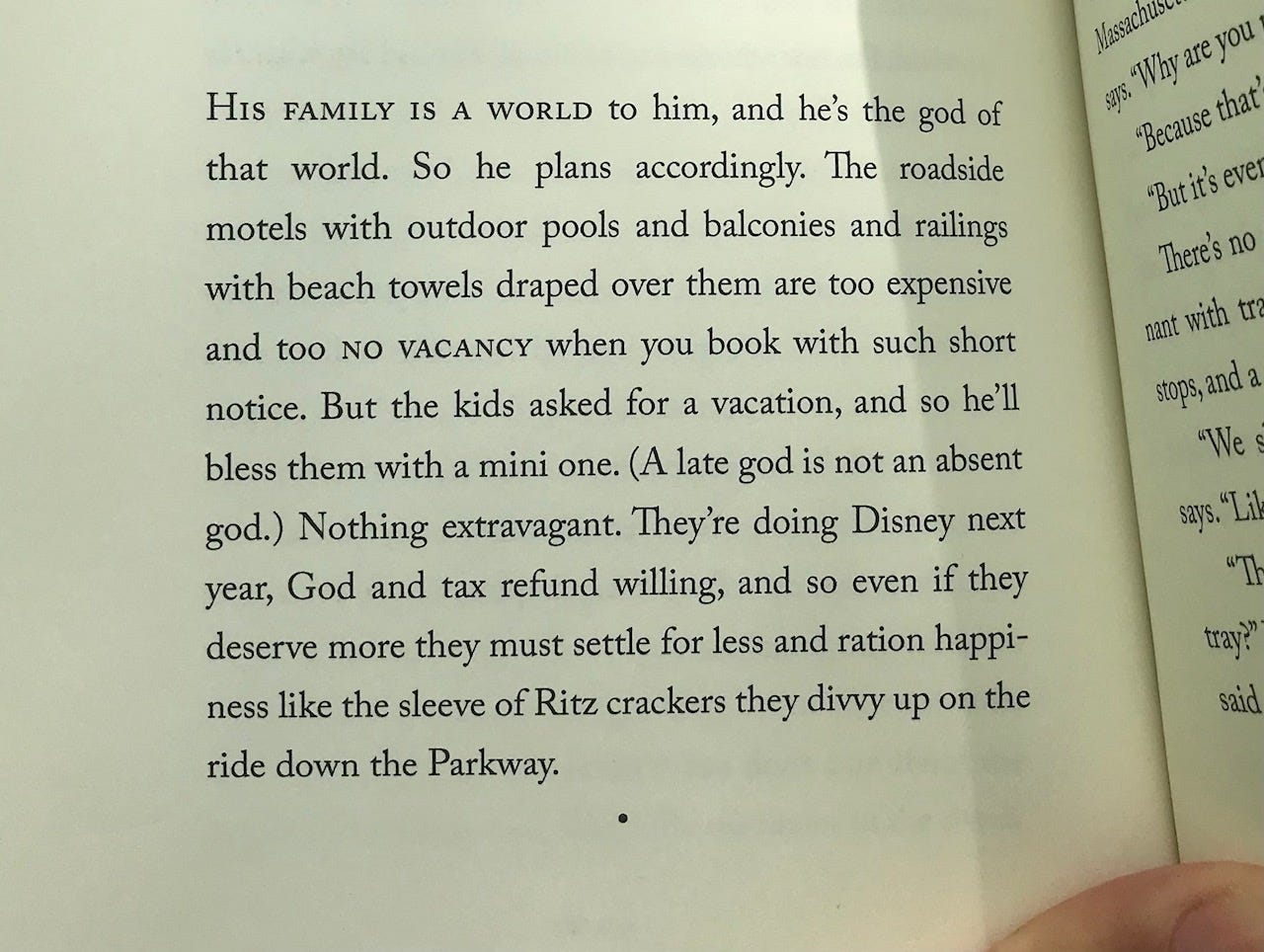

Joe: Keansburg entered my consciousness probably a dozen years ago. My wife’s itinerant father stayed in an apartment there for a few years. I’d never heard of the place at that point. Then maybe six or seven years ago we were looking for somewhere to visit down the shore for a night or two that wouldn’t break the bank. Keansburg was trashy in the way a lot of Jersey Shore towns are trashy, but it was clearly a cheaper option than, say, Seaside Heights. We stayed at a motel right on the highway, and I remember sitting up in bed with one of those clip-on book lights reading Barry Hannah (I think I had taken Ray out of the library) while my wife and kids slept.

We went to a shitty diner for breakfast the next day, maybe half a mile from the motel, and we entertained ourselves at the Keansburg boardwalk, which isn’t really a boardwalk seeing as how it doesn’t parallel the shoreline. It’s just a rinky-dink amusement park. There’s a water park, too. It’s just a great place to visit on a budget. For whatever reason, that weekend stuck with me, and it evoked something when I thought about it. Reading Ray might also have had something to do with it. I felt like I was living Barry Hannah’s prose — in the pace and patterns of my movements — and I’d like to think I caught something of that feeling in “Super 8,” the story that takes place in Keansburg. “Super 8” doesn’t take place in a mom-and-pop motel though, but rather a corporate hotel chain, so it’s a different valence. I wasn’t aware of any of that history you mentioned, but it makes the Keansburg I’ve come to know seem even more tragic.

Pete: What is your favorite artistic rendering — literary, musical, filmic, whatever — of New Jersey?

Joe: My favorite renderings are the ones I feel are the most authentic. The state isn’t overrun by mob murders, obviously, but the minutiae, mannerisms, and nuances that David Chase was able to summon for The Sopranos…it’s the exemplar by which any other depiction should be measured. Kevin Smith has done an impressive job on screen as well, though with more of a South Jersey focus. His dialogue — though not always delivered by the most accomplished actors — replicates what you might encounter in conversation with the commonfolk of Monmouth or Ocean County. Clerks elicits a familiar suburban malaise, and the diner and skee ball scenes in Chasing Amy meet the criteria.

As for literature, Philip Roth will forever have Newark on lock. But Junot Díaz can claim Hudson, Passaic, and Middlesex Counties, depending on whether you’re reading his short fiction or Oscar Wao. As for music, I can’t help but feel intense pride when I listen to MCs from Jersey who proclaim their roots and revere their cities. That would include Redman, Naughty by Nature, the Artifacts — all those heads from the Oranges and Newark. I went with my kid to see Lauryn Hill perform last fall. She had home footage and photographs playing on the screen behind her at one point, and that shit was emotional. She even had her high school’s marching band playing in the aisles for a couple songs.

We can look further south, too, to the Trenton contingent — Poor Righteous Teachers and YZ and the like. I’d argue a beat by Tony D is as evocative of the Garden State as anything in Springsteen’s discography. Expat Sharon Van Etten crafted an indelible New Jersey anthem several years ago with “Seventeen,” though I don’t think many people other than myself read it as such.

Pete: You published Mixedbloods and Bad Days on the Batsto via Fomite, an independent publishing collective. What about their model appealed to you? Were there any challenges in terms of bringing your books to market, or finding readers? Do you work with editors?

Joe: Like with most independent literary presses, I submitted a manuscript to Fomite and crossed my fingers. What made Fomite different from the countless other presses I’ve attempted to publish with is the fact that it’s a husband-and-wife team who respond personally to these submissions and inquiries. They fancy themselves a “post-capitalist operation,” in that the authors are entitled to nearly all of the profits. Fomite only takes a cut to cover production expenses. They’re in it for the right reasons — for community-building, in particular. That’s what appealed to me. As soon as I came across their website, I felt like it was the best place for my work, and it has been for two titles now.

Marc Estrin and Donna Bister are radicals, and their politics align with my own. They’ve published the work of Peter Schumann, the founder of the Bread & Puppet Theater in Vermont, a collective which they’ve been a part of for decades. I worked with Marc as editor on both the titles I’ve published with Fomite. I found his suggestions to be incisive. I adopted many of his recommendations, but I can also be obstinate about my work and insist on maintaining my vision for the book when I feel it’s the right approach. It’s always a challenge to find a market for your book, to find readers — especially with fiction. Like most indie presses, Fomite lacks the resources to promote their books as much as they’d like to. But I’m of the mind that there’s merit in having the book out in the world even if it doesn’t immediately meet a mass audience. I’m comfortable writing books and placing my faith in the seekers. Fuck a Kirkus review.

Pete: I imagine Caltrops is occupying most of your free time these days. Were you involved in zine culture as a younger writer? How did you arrive at the Caltrops format? Who’s your target audience, and what’s been your experience promoting it hand-to-hand?

Joe: Caltrops was intended to be a way for me to get back into writing about music before I started working steadfastly on the book I’d been researching and conducting interviews for, which is my book about the Anticon collective. Caltrops, I figured, would get me in the correct headspace for that. Geng PTP — who I had interviewed for that aforementioned book — sent me the Paraffin tape and some of his own King Vision Ultra shit (Pain of Mind), and I was stunned to learn music like this was being made at that moment and I felt drawn to write about it. Caltrops grew exponentially, and the positive feedback was fast and effusive, and my introduction to an array of active artists made it clear to me that I needed to keep writing under the Caltrops banner. Like all the best things in life, I had zero expectations going into it, yet it spawned something spectacular and fulfilling.

My target audience is the underground hip-hop community — fans and artists alike. Making sure that Caltrops existed in a tangible form was crucial to that. I wanted to rediscover the sense of community I’d felt as a young man back at the turn of the millennium. Fortunately for me, an underground moment seemed to be emerging just as I dove back in. It’s the perfect mix of new, emerging artists with all the youthful vim and vigor you’d expect from that set, coupled with those of us in our 40s who have been inspired to look back on what it was we once had and feel motivated enough to build new monuments. The experiences I’ve had at shows in NY, NJ, and Philly over the past four years or so have been so validating. To meet fellow fans of this music, and fans of what I’m doing with Caltrops, and being able to hand them a copy of a zine that I made in my kitchen is deeply rewarding.

Pete: One of the cool things about Armand Hammer is they have such a sprawling discography, it seems like every listener favors a different project (or era, if you will). And I feel like that makes them uniquely suited for an undertaking like Caltrops. Which are your favorite among woods’s records? Got a power ranking?

Joe: Well, I’d definitely say I favor the moment they’re in now, which I date back to Paraffin. That’s not to say I don’t appreciate Rome, but Paraffin was my proper introduction to their work, so it and the work that has followed holds a special place in my critic’s heart. I’ve only listened to Race Music a bit, but it seems a bit over-bloated with inconsistent production, or at least it includes sonics I’m personally not so keen on. From woods’s catalog, I think Aethiopes and Hiding Places are the high-water marks — the most cohesive album visions.

His earlier solo work, I feel, suffers from the same problems as Race Music. To my ears, production wasn’t great, in general, during the 2000s and early 2010s. His earlier solo projects have gems, no doubt, but his tone, cadence, and delivery aren’t as refined as we find them to be today. I recently explored all of the Super Chron Flight Brothers albums, and those really didn’t click for me. That work represents an inchoate and turgid version of what’s to come later. I think it boils down to artistic maturity. It’s the difference between the “typewriter” font on the original History Will Absolve Me cover and the more austere and artful version of the cover for the 10-year anniversary reissue.

ELUCID, on the other hand, seems to have been an accomplished vocalist since he first stepped in the booth. I Told Bessie remains the premier album for me. I Told Bessie motivated me to go further back in his catalog. I appreciate Shit Don’t Rhyme No More and Save Yourself, but I’m particularly fond of his shorter, EP-length projects (Osage; Valley of Grace; Every Egg I Cracked Today Was Double Yolked). ELUCID is more of an experimental musician than woods, and you can even hear that in the eclectic musical backdrops he’s fucked with over the years. I’m glad he’s brought those sounds into the Armand Hammer sphere. I don’t remember if I said it myself or if I read it somewhere, but the idea of woods as a novelist and ELUCID as a poet can be a reductive appraisal. They both inhabit qualities of each — novelist and poet — in their writing. At the risk of perpetuating yet another reductive comparison, I think of ELUCID as a jazzman and woods as a bluesman, though each traverses into the other chamber at times.

Pete: I dig that — I feel like their early work gets glossed over in the latter-day coverage. I remember listening to Super Chron Flight Brothers when I was in college and absolutely not getting it. Like, I knew there was something there that was just not clicking in my teenage brain, and I kind of avoided woods for a while after that.

My favorite project of theirs, by a pretty wide margin, is Terror Management. Feels like I’m the only one who liked that record, there’s a calmness about it that sets it apart. I like how they’re always tinkering, how they’re exacting geniuses without being perfectionists, and I feel like so much of the writing about them fails to capture that, and does them a slight disservice. So, I appreciate this.

Joe: I feel you on Terror Management. I would rank it just below my top two. “Western Education Is Forbidden” is easily one of my top woods solo tracks. And, as an addendum, an earlier work from Armand Hammer that I really love is the Furtive Movements EP, which I think I listened to on the heels of receiving that Paraffin tape from Geng. I played it on my ancient iPhone through my primeval Bluetooth speaker while preparing my vegetable garden in early spring. “Touch & Agree” hit an emotional register that I hadn’t yet heard from them, and I had to drop the fistfuls of weeds for a second and just take that shit in.

Pete: Can you tell me about the Anticon project? Have you conducted any particularly eye-opening interviews? Approached any publishers? When will you know you've finally finished such an ambitious, sprawling book project?

Joe: You referred to it as my white whale, and that’s not so far off, but I do intend to fare better than Ahab when all’s said and done. If someone had told me ten years ago that I would write a book about an underground hip-hop collective and it would take the better part of eight years from conception to birth, from germ to epidemic, I would’ve never believed it. I get impatient with writing projects — be it a book or a poem — but rushing to finish something rarely yields good results. So I’ve really had to discipline myself when it comes to this one. I want it done right, and so that’s what I plan to do. It feels really good to know I’m nearing the end — I’m anxious to share it, but, of course, I also fear no one will care. That anxiety is likely in direct correlation with the amount of effort I’ve put into the project. Wisely, I put some clear parameters around the project in terms of the years I wanted to cover (roughly 1997-2002). I know I’ll be done when I’ve written about all the songs and albums I desire to, as well as all the historical narrative work that falls in between that music. Oh so close.

I have to assume that there’s going to be something in the book for every underground hip-hop fan. If you’re into Caltrops-style analysis of the music, there’s plenty of that. If you’re nostalgic about the scene as we inched toward a new millennium, there’s that too. The book is both oral history and critical engagement with a body of work, so if you tire of my analysis you can appreciate what the artists themselves have to say about everything (Check the Technique style). One of the theses of the book is how the underground community is truly a network, so I don’t simply talk about Anticon. Many other names of that era appear in its pages, and that will hopefully appeal to a wider audience (even including Anticon’s detractors).

Learning how to conduct interviews (almost entirely over the phone) was a trip. Listening back to those earliest interviews for the purpose of transcribing them was a special kind of hell. By interview #83, I started to get the hang of it. I came into this book with a lot of knowledge on my subject, but I was constantly surprised by what I learned from the conversations. There were people who I thought served relatively peripheral roles to this time period, only to find out they were crucial to its success in various ways. I was touched by the honest and emotional moments that took place during some calls, and I felt honored to provide a platform for others to speak about this time in their life and the music they made in a manner they’ve never been given the opportunity to. Sorry for being so vague, but I don’t want to reveal too much too soon.

I have not approached a single publisher. I decided some time ago that I would publish this book under the Caltrops Press imprint with the belief that it would make the most sense; it will be in the same independent-as-fuck spirit as the work I’m writing about. Countless people have asked me, Why don’t you just do a podcast? Well, I’m after something more substantive. Always seeking permanence, immortality. A fool’s errand, but here we are. The long-term goal is for “Caltrops Press” to become a publisher of books on the subject of hip-hop after the release of the Anticon one, but don’t let me get too far ahead of myself.